Aromatic compounds differ from aliphatic compounds in that they contain a benzene ring. Hückel's rule refines this by stating that if a cyclic, planar molecule has 4n+2 π electrons, where n ∈ ℤ+, then it's aromatic. And if you're asking yourself how we ended up with algebra, then you're in good company.

There are various different types of electrons, depending on which bonds they form in a compound. π electrons form π bonds from the sideways overlap of p orbitals - but how many of these bonds could be formed?

In benzene, each carbon atom has four valence electrons. It uses two of them to bond with an adjacent carbon, one to bond with a hydrogen atom, and the other becomes part of an electrondense ring above and below the planar structure. Hence you get six π electrons available, and 6 = 4(1) + 2, so we can conclude that since benzene is also cyclic and planar, it satisfies Hückel's rule and thus benzene is an aromatic compound. The same applies for phenol, benzaldehyde, and phenylamine, amongst other arenes.

A quick example to demonstrate how Hückel's rule can eliminate aliphatic compounds is by looking at cyclohexane. Here, each carbon bonds to two carbons and two hydrogens, thus there are no available π electrons left. So cyclohexane may be cyclic and planar, but it isn't aromatic - it is thus merely aliphatic.

And if you were wondering why it's 4n+2, it's to do with how orbitals are arranged in aromatic compounds. Two electrons fill the lowest possible energy level, and every subsequent energy level is occupied by four electrons - these electrons are all paired up in the orbitals, which is why aromatic compounds are so stable.

Now it's an unspoken rule at A Level chemistry that the two shall never cross. My reaction pathways diagram has no arrows pointing between benzene and an alkene, for instance. But what if you could cross this large bridge? Well, you'd somehow have to form a compound that would satisfy Hückel's rule. On paper, this seems easy. My first thought would be this reaction:

C6H12 → C6H6 + 3H2

This reaction would involve converting cyclohexane into benzene by dehydrogenating it. Perhaps surprisingly, this is doable, with the use of a platinum catalyst. This Nature article discusses the process in greater detail, however it essentially states that this reaction is a great way of accessing hydrogen to be used as a fuel. Cyclohexane and benzene can both act as reversible liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHC), so can store hydrogen to be released in the process of a reaction like this, and the stability of platinum makes it an effective catalyst for this reaction. In fact, the reaction can have a 100% conversion rate at 350℃, with low feed rates of cyclohexane of about 0.01 mL min-1. The article goes into greater depth and makes for a curious read.

|

| The aromatic estradiol... |

|

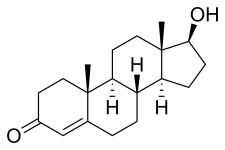

| ...and the aliphatic testosterone |

And thus it's rather clear that the aliphatic and aromatic worlds aren't that separate, especially considering one becomes the other in our bodies. It's all rather fascinating and confusing in exactly the same way, which often comes with learning chemistry.

Comments

Post a Comment