One of my favourite blogposts is on benzene, which I wrote some 18 months ago. In fact, I clearly remember writing the first draft of the post before I had to set off for a family holiday to Cornwall; we were gonna leave early, so at 6am I decided to write up most of the post right up to when we were about to leave. Simpler times.

However, since then, I've actually done an A Level in chemistry, as well as one term studying chemistry at uni, and even if my A Level was underwhelming, over time I have realised I was, at times, incorrect, or at least vague when it came to the blogpost. I've decided to set the record straight on various points in the post, as well as also perhaps giving some new information on certain topics.

- The structure of benzene

This is extremely important to address, because benzene isn't a straightforward molecule whatsoever. You can't really say it adopts a certain structure, because benzene itself is rather mysterious. Take the Kekulé model below:

And contrast with the Pauling model:

They kind of say the same thing, it's just not obvious.Electrons don't really exist in a confined space, at the quantum level at least. A double bond might suggest the electrons in that bond are stuck between the carbon atoms, and could at best move in between the two, and in the case of a simple molecule like ethene, where there is one C=C double bond, that is what will happen. But take a more advanced molecule like 1,3-butadiene (CH2=CH-CH=CH2), and you've got alternating single and double bonds, and things start to get slightly confusing.

|

| 1,3-butadiene. Simple example of delocalisation. |

A double bond is a graphical representation of a π bond, which forms when two p orbitals overlap sideways with each other. As you can see in 1,3-butadiene, there are three carbon atoms in a row which have a π bond in some way or another, which means they all have π electrons - which are...electrons present in a π bond. So the electrons in the p orbitals here can be shared between each other - this is known as delocalisation, where electrons don't necessarily exist in a specific, localised region. And look, I did mention that in the original post, but only within the context of the Pauling model. But the Kekulé incorporates this idea, as well.

Basically, when you have delocalisation, you can have alternative structures because those π bonds can be present in different areas due to the movement of electrons between p orbitals. This is known as resonance, and benzene has two resonance structures. They're not actual structures, really. Neither is preferred over the other, and the actual structure is the average of the two. So yes, you could argue the Pauling model is the best model because it acts as an average of where the electrons could be, but that doesn't mean the resonance model of benzene is problematic - if anything, it's more realistic.

Now, that's not all there is to resonance, but when the topic is benzene, that's it.- The phrasing of benzene

I mentioned a couple times that benzene is present in various molecules - that's wrong. Very wrong.

I mean, benzene's a carcinogen. It can cause headaches, dizziness, anaemia, leukemia, loss of consciousness, and death. No way in hell will you find it in aspirin. What you'll find instead is a phenyl group (C6H5-), which is similar except it's a benzene molecule bonded to another molecule. And that makes a massive difference. Similar with phenol, which I mentioned had benzene, which isn't true really - yes, it's a hydroxide bonded to a phenyl group, but chemically, they're very different. Phenol isn't even a carcinogen, I mean that's a difference.

(And yes, I'm aware something being carcinogenic isn't exactly tied to the chemical formula - sometimes it's something different. Carbon monoxide can cause cancer because it's a stronger ligand than carbon dioxide, so binds more strongly with haemoglobin than carbon dioxide would. And yet they're very similar in formula.)

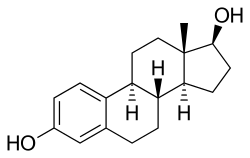

- Estradiol

This is a specific section, but most of the points from the previous section still apply.

Estradiol is a steroid that stimulates the production of estrogen

...sort of. I did cite a source for this, to be fair, but it was a book I gave back ages ago, and it's at my old school anyways. I'm not going back for it.

Is estradiol a steroid? Chemically, it is.

Yes, there is a definition for steroid! Basically, a steroid is a structure with four fused rings arranged in a very specific way. As below:

|

Other bonded structures are available |

stimulates the production of estrogen

This is more a language quirk. Yes, estradiol and estrogen are effectively the same. They have the same chemical formula. But estradiol is also technically an estrogen, and it just so happens in English that everyone refers to estrogen to refer to estradiol and vice versa. Now I know this is extremely pedantic, but technically when I said that line, all I was saying was "a subset of estrogen causes more estrogen", which is meaningless.

More importantly, I was referring to estradiol as medication, which I didn't make clear at all. So that maybe made the sentence a bit more confusing.

And again, there is no benzene in estradiol or estrogen - that would be catastrophic! Instead, there is a phenyl group which bonds to the ring. That is important, because again phenol and benzene have numerous different chemical properties.

- Substitution reactions

I should have been clearer with this point.

Benzene undergoes substitution reactions for the most part. Indeed, this is also another reason why it can't contain C=C double bonds - if it did, it should undergo electrophilic addition reactions, yet it won't.

This only really works if you abandon the Kekulé model entirely and believe the Pauling model is the be-all and end-all. Which, as I mentioned earlier, isn't true. Benzene does have p orbitals overlapping and forming π bonds, after all. The main reason benzene won't do these reactions is due to its stability.

- Graphite and graphene

In retrospect, I have no idea why I brought this up in the actual post. Yes, in theory losing all your hydrogens but retaining your delocalisation could in theory relate to benzene. But I have no idea what that has to do with electrophilic substitution. Furthermore, yes graphene is aromatic, but it's not the same type of aromaticity as benzene, apparently. So again, very misleading on my part.

- Conclusion

I'm not sure what I'm hoping to achieve with this post. Truth be told, if I ever write about chemistry on this blog, it will almost always be for revision purposes. I only wrote them for my personal statement, likely never had them read by my interviewers, and I keep them up because, well, that's what I do, I like archives.

But I do think things should be corrected, after all if they're not, then they run the risk of misleading people. And to be fair...I don't think all these errors are my fault. Why would I know there are four types of estrogen, and the main one - estradiol - not only has the same name, but is merely a subclass?

Well I should have known, part of the job is to research. And I didn't do that properly. But again, there's nothing really wrong with getting something written, especially if it's more factually correct.

Edit: great, I only just realised benzyl means something completely different. Hopefully no one noticed that.

When I first started reading your blog a year ago, most of the chemistry went over my head. But now that I've done organic chemistry, I've been using your posts for revision. Thanks for the correction!

ReplyDeleteWould also like to bring to attention: I've since corrected the molecular diagram in the ozone blogpost: https://allovertwoa.blogspot.com/2024/05/ozone.html

ReplyDeleteBringing this up here since, well...it's a corrections post. But otherwise it looks okay