Try you might, you'll never be far from carbon. That's partly because you are a carbon-based lifeform, but also because all of biochemistry and organic chemistry depends on carbon. And also because carbon is present in loads of fields of industry. And also because carbon itself is the 4th most abundant element in the universe. It's a bit scary once you realise how important carbon really is.

|

| Carbon (graphite) |

Hell, carbon is essential to the very definition of chemistry itself. The mole - a unit that basically defines the quantity of something in chemistry - used to be defined as the amount of atoms of 12g of 12C. And 12C itself is used to define atomic mass, where 1/12 of the mass of 12C is equivalent to one dalton, or about 1.66x10-27 kg. The dalton is essentially used to convert between the relative atomic mass of an element (which for carbon would be 12) and atomic mass.

|

| Carbon (diamond) |

Electronic structure

Carbon's managed to come this far because of how great it is at bonding with other elements. Carbon's electronic composition is this:

1s22s22p2

Note that you have three p orbitals in total. Which means carbon has one fully filled 2s orbital, along with two half filled 2p orbitals, and one empty 2p orbital. This is important to remember.

This gives carbon four valence electrons in its outermost orbitals to play around with, and it can be extremely versatile with them. This all depends on the hybridisation state of carbon. Put simply, you can combine s and p orbitals with each other to form new orbitals which have equal energy levels to each other:

- Take the 2s orbital along with your three 2p orbitals, and combine them together. You'll end up with an sp3 hybridised carbon. This means the carbon has four bonding regions around it - expect to see four σ bonds around the carbon, typically C-H or C-Cl bonds, amongst others.

- Now take the 2s orbital, and combine it with just two 2p orbitals. The resultant carbon is sp2 hybridised, and the carbon has three bonding regions present. Expect the carbon to form three σ bonds, as well as one π bond by using the unused p orbital.

- The π bond also means you can expect to see double bonds crop up, such as C=O bonds like in aldehydes, or C=C bonds in alkenes. This arrangement is similar in aromatic molecules like benzene.

- Finally, combine the 2s orbital with one 2p orbital. This will give you an sp hybridised orbital, where the carbon can form two σ bonds. This also leaves the other two 2p orbitals free to form two π bonds.

- sp hybridised carbons typically form triple bonds with other atoms. Examples include C≡C bonds found in alkynes, as well as C≡N bonds in cyanides and C≡O - better known as carbon monoxide.

And thanks to this, carbon is everywhere. In the air, in the water, on land, in space, in your body. And you can't do anything about it.

Organic and biochemistry

Carbon's responsible for organic chemistry. The whole field exists purely to focus on carbon-based compounds, and considering how versatile carbon already can be, it's impressive how far you can get. You thus end up with various different compounds characterised by a certain functional group, and each of these compounds merely differs by how many CH2 groups you have. This is called a homologous series:

- With sp3 hybridised carbons, you can form several C-C, C-H, C-O, or C-X (where X is a halogen) bonds, amongst others. This gives you alkanes, alcohols, and alkyl halides.

- sp2 hybridised carbons open up the possibility of double bonds, and this is where you can get alkenes (C=C) and carbonyls (molecules with a C=O functional group). And there are so many types of carbonyl I could write an entire blogpost just listing them. But the most recognisable ones are aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, amides, and esters.

- That's not forgetting about benzene, which is a very large can of worms. Benzene's unique because whilst it does have an sp2 carbon, it also consists of a ring of delocalised electrons, one for each carbon. This delocalisation does affect the reactions benzene undergoes compared to other sp2 carbons. More on benzene in these two blogposts.

- sp carbons are more limited in scope, indeed I've already mentioned most of the key examples earlier.

You can have additional compounds from this list as well; take a carboxylic acid, bond it to a carbon which is itself bonded to an amino group, and you get an amino acid. And those amino acids can bond with each other to form peptides and proteins. Now you have life, partially thanks to carbon. That's without mentioning carbon's essential role in metabolism, or its presence in carbohydrates and sugars such as glucose, which we use up in respiration. I've not done enough biochemistry to discuss that in depth, though :p.

Allotropes of carbon

Sometimes, carbon doesn't bond with other elements - it bonds with itself. And since carbon is capable of forming various different bonds due to its hybridisation states, you can get many different forms of carbon. These are known as allotropes of carbon, and vary by look, hardness, and various other physical properties.

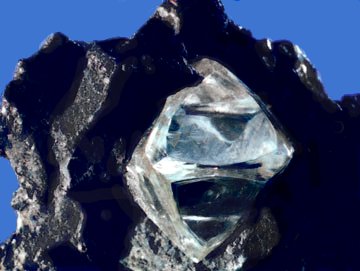

Take diamond, for example. It's a strong material, a poor electrical conductor, and shiny. Chemically-speaking, the carbon atoms are arranged in a repeating crystal structure, four bonds to a carbon, and each crystal is packed close to each other. This is a structure known as diamond cubic. Imagine a cube - you have a carbon atom on the corners of the cube, as well as one atom in the middle of each face. Between those atoms, you also have another atom roughly between them. Draw bonds between them, and you have a diamond cubic. In theory, this structure can go on forever.

|

| Diamond |

Alternatively, you can have graphite, which is dull, brittle, but makes for an excellent conductor. This is because in graphite, each carbon atom is bonded to three other carbons, sort of like a honeycomb. That leaves one electron per carbon to become delocalised, and that gives graphite a charge carrier. Between each layer of graphite are intermolecular bonds, which is how you build up the layered structure of graphite - and again, this could in theory go on forever. One single sheet of graphite is known as graphene, which is stronger than graphite because there are no more intermolecular bonds to break.

|

| Graphite's surface structure under a microscope. Scale reads 0.5nm. |

You can also go from graphite into diamond if you place it under high pressures at high temperatures. So in theory you could convert pencil lead into wedding ring accessories if you so wished. In fact, graphite is thermodynamically the most stable form of carbon.

You could also take those carbon atoms and effectively wrap the bonds around around to form a tube, known as a fullerene. Roll up a sheet of graphene into a cylinder and you form a carbon nanotube. Alternatively, you can take those carbons and form a spherical structure. This is how you can get C60, or Buckminsterfullerene, a spherical fullerene which kinda looks like a football.

|

| Carbon nanotube |

The rest of Group 14

Carbon itself is somewhat different to the rest of group 14, which might seem surprising considering that in general, most elements in a group are at least similar to each other. But no, carbon is a real outlier in a group also consisting of silicon, germanium, tin, and lead.

The most obvious port of call is that carbon isn't a metal, whereas the rest of the elements at least act like they are. Okay, silicon and germanium are metalloids, but that means they have metallic characteristics, which carbon completely lacks. This is also how you end up with carbon dioxide (famous greenhouse gas) and silicon dioxide (sand) being so different to each other, and lead dioxide (battery cathode) is very different to both as well.

But there are also less obvious differences. Consider catenation, which is the tendency for an element to bond with itself as part of a compound. Carbon does this loads - just consider alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, and basically every single organic compound. But go down group 14, and this becomes way less common. This is because the C atomic radius is far smaller than, say, Pb's, so any atomic overlap between C atoms will be greater than in Pb, where the orbitals are far more diffuse.

Then there's the fact that carbon won't budge on its tetravalency, since it has no low-lying d-orbitals to help it out. In silicon and beyond, those d-orbitals end up being lower in energy, so can be used to expand the octet and produce various different valencies.

The silent killer?

Carbon being so ubiquitous inevitably means it's easy to get scared of it. Everyone's heard of carbon footprints and having to manage how much carbon you use, so as not to exacerbate global warming. Part of that is simply due to carbon being, well, everywhere.

|

| Battersea Power Station. Used to burn coal, which is mostly carbon. |

Before I started writing this post, I thought coal was fully carbon. Turns out it's not - coal is majority carbon, but there are traces of hydrogen, sulphur, and other elements there. And coal's been pretty fundamental to energy production ever since the Industrial Revolution, with coal mining being a massive industry up until the 1980s in the UK (though it ended for non-climate related reasons). Turns out, burning coal leads to the production of carbon dioxide in complete combustion, or carbon monoxide/soot in incomplete combustion - the former is terrible for the atmosphere, the latter is deadly. It's estimated coal causes around 800,000 premature deaths annually as a result.

But then you look at other sources of energy production, such as crude oil and natural gas, and they all involve carbon one way or another. The former through fractional distillation of hydrocarbons to produce petroleum and naphtha, amongst other fuels; the latter is 95% methane. Along with coal, they are fossil fuels, and burning them causes various issues, enmvironmental and health-related. Hell, you even have graphite in nuclear reactors which acts as a moderator in the reactor core. It really is everywhere.

Conclusion

I could go on about carbon and its various uses, but chemically, that's about it. The truth is, carbon is so ubiquitous everywhere, it's easy to forget just how prevalent it is. After all, you wouldn't live without carbon, that's how vital it is, and in a way, we just take it for granted.

Carbon really is the main character element.

Truly the goat of elements

ReplyDelete